In Modesto, Calif., utility records chart an 18 percent rise in farmers’ energy use in 2014 compared with 2013. No evidence shows exactly why this happened, but California’s drought, now in its fourth year, sent many farmers to their wells to pump from hidden aquifers water that normally would be found at ground level.

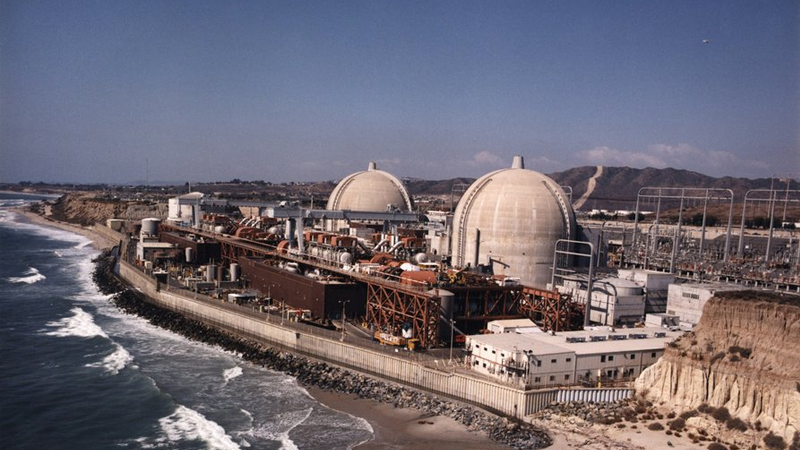

Such measures are a timely illustration of the way water needs power — not just to move it, but to clean it and even, with desalination, to create it from brine. A large desalination plant being built to provide 7 percent of San Diego’s water will require about 38 megawatts of power, enough for more than 28,000 homes. And it is no coincidence that primary owners of the 2,250-megawatt, coal-fired Navajo generating station near Page, Ariz., are water managers; they need the power to move water.

The converse is also true: Water is required for power — for hydropower; for extracting oil, natural gas and coal; and, most of all, for cooling power plants. A report from the Congressional Research Service projects that 85 percent of the growth in domestic water consumption from 2005 to 2030 will come from the power sector.

In 2011, Texas suffered its own blistering drought. Kent Saathoff, then a vice president of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, warned at the time that without rain in the coming months, “there could be several thousand megawatts of generators that won’t have sufficient cooling water to operate.” Rain eventually arrived to avert that disruption, but this year the R.W. Miller 403-megawatt plant in Palo Pinto, west of Fort Worth, went off-line because it lacks sufficient cooling water.

Coiled throughout the American economy, energy and water are forever linked, an economic version of DNA’s double helix. As populations grow and climate change and droughts take their toll, resource managers and environmental advocates are warning that scarcity of either water or energy could set off shortages and escalating costs for both.

“One of the serious risks is that we accelerate a very damaging negative feedback loop both in protecting the environment and impacts to our economy,” said Vickie Patton, general counsel at the Environmental Defense Fund. She worries that “we will be using energy and water alike in a fashion that only leads to more serious impacts, greater use and much higher cost.”

The situation was born of assumptions from the last century about the abundance of both power and water, according to the Pacific Institute, a nonprofit research center based in Oakland, Calif. Now those assumptions are in doubt.