Not long after walking onstage Thursday night at Madison Square Garden, Louis C.K. made an announcement: “I have a joke.” Then he told the oldest one on the playground: “Why did the chicken cross the road?”

As with so many of Louis C.K.’s bits, it’s impossible for anyone but him to do justice to the intricate punch line — the long explanation hinged on a racist chicken and a black pedestrian — but it established a back-to-basics tone for this relentlessly funny set, his best since the special “Hilarious” in 2010.

It’s not axiomatic that fame detracts from an artist’s stand-up, but it happens. Wealth and celebrity challenge a comic’s ability to be relatable, but more important, developing new material is labor-intensive and working in movies or television can steal your focus. It’s a particular obstacle for Louis C.K., because besides maintaining a furiously busy schedule, he famously throws away all his material every year or two and starts anew. That’s why fans of his stand-up will find this show (which he performs again on Monday and Thursday) such a wonderful relief.

Between the absurdist flourishes of his FX series “Louie” and the bleak tragedy of his web series “Horace and Pete,” it’s easy to forget that the restless mind of Louis C.K. is the greatest delivery system for jokes today. His stand-up is as insightful as his television work, but it’s always been more ruthless about laughs, particularly this assured new hour and a half of material, veering from corkscrew one-liners and broad sex gags to garden-variety observational humor and twisty yarns dense with jokes.

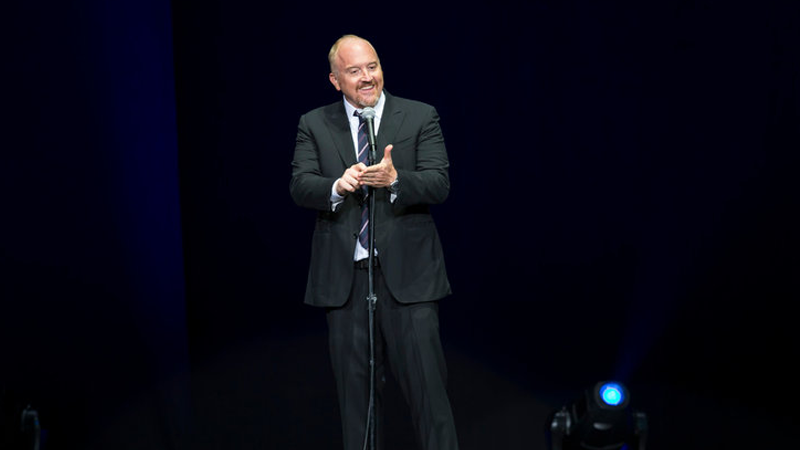

Dispensing with his usual jeans and a T-shirt, he wore a skinny tie and a black suit, a costume that made him look less like a slovenly everyman than the showbiz star that he is. But don’t let the new image fool you. He’s returning to his trustiest subject matter: grousing dad humor, bleak jokes about romance and loneliness, gay fantasy (his bit about lusting after Ewan McGregor has a superior sequel with the stars of “Magic Mike”), vignettes empathetically imagining the perspectives of the least likely people, and racial humor dancing up to the line of bad taste before a confident pirouette.

No one finds comedy in the perverse with more ingenuity. In one inspired take on the members of ISIS who behead their captives, he suggests that they don’t like bald victims as much because it’s more difficult to hold their severed heads aloft. That’s positively cheerful compared with his dominant theme of the night: Suicide, which he normalizes, recounting the many times we think of it. In the middle of a paean to naps, Louis C.K. tosses out this strange description: “It’s like you get to kill yourself and take it back.” Only Louis C.K. could make you wonder: Did he just deliver a mundane ode to the nap as an excuse to bring up a defense of suicide?

In his personal stories, Louis C.K. rarely plays the loser anymore and is more likely to present himself as a smug or entitled bore. But he has not abandoned his aggressively dour worldview and resolute pessimism, particularly when it comes to romance, which he portrays as ephemeral and doomed to curdle into tension and ire.

He approaches this theme from myriad directions, sketching the subtext-rich relationship of an older couple, complete with characterizations and details of clothes and personality that reveal his gifts as a dramatist. The way he portrays their relationship, both in old age and the afterlife, begins modestly and evolves into a lovely and melancholy playlet. He also tries a personal story, mulling the absurdity that the reason he had kids, the source of his greatest happiness, was to avoid a fight with his wife. And he even makes his point through math: “Love plus time minus distance equals hate.”

This may sound like a downbeat show, but isn’t. There are hopeful notes, strategically placed, and frequent shifts into crowd-pleasing bits. As in his last special, which was recorded at Madison Square Garden, he incorporates a multitude of goofy voices, this time including a hammy Bela Lugosi-style vampire, an Elizabethan Lothario and a slew of stereotypical characters that he says stuck in his head since he was a kid watching old television shows. “Stereotypes are harmful,” he says. “But the voices are funny.”

Louis C.K. may be producing comedy about his usual obsessions in a familiar style, but where he has matured is in how he builds a set, putting on a clinic in developing themes and making transitions. The way he ties the personal with the philosophical, or hides a transgression inside an involving story or rigorous train of thought, looks effortless. But it isn’t.

As talented as he is, this is the kind of taut, elegant comedy that can only come from many hours of refinement onstage. And the polished performance has little of the spontaneous and freewheeling style of a comedy club set. It’s the work of a seasoned, elite pro determined to prove that he hasn’t lost a step.